|

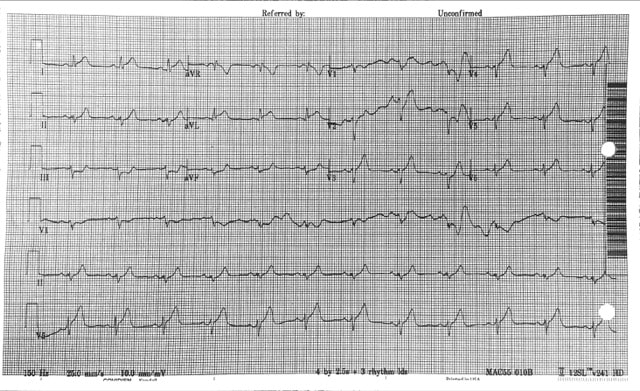

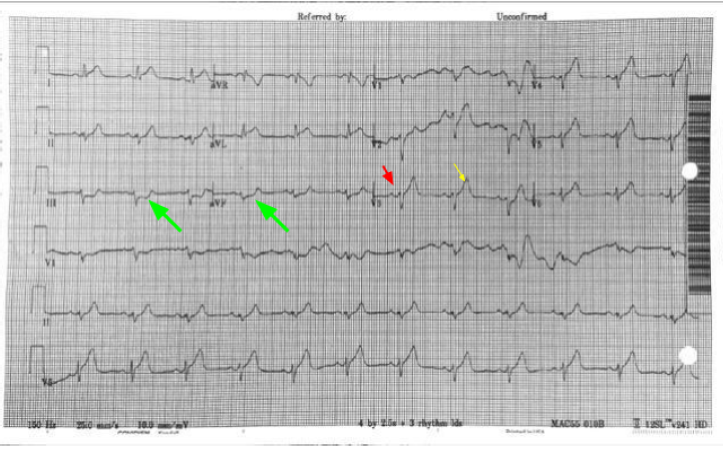

61 year old presents to the ED with chest pain radiating to his shoulder What is the diagnosis?

Why Not...

Why is this not Benign Early Repolarization?

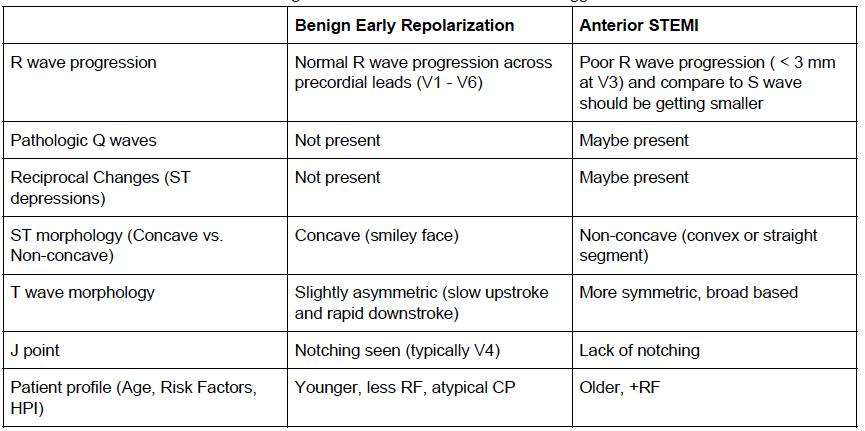

The differentiation of benign ST elevations (BER) and Anterior STEMI can be difficult. There are a number of characteristics which are suggestive of BER vs. STEMI. Make sure to examine for other ischemic changes. Our job is to exclude MI and BER should be diagnosis of exclusion. Some features suggestive of each in below table. Learn more

Consider using the Subtle Anterior STEMI calculator in cases where you are concerned, but the EKG may be difficult to decipher

0 Comments

Mechanical Complications Treatment for mechanical post-MI complications includes vasodilators and ACE inhibitors, as well as blood thinners in cases which have thrombi.

Ischemic Complications

Pericarditis

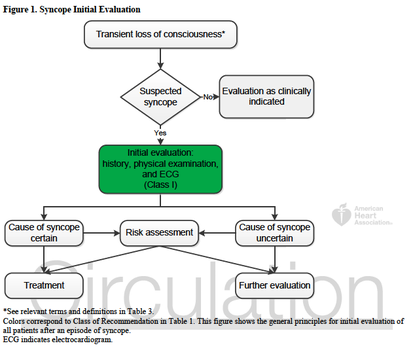

In-line with the month’s cardiology theme, this note from the TR desk will discuss the evaluation of syncope, and the brand new (2 days young) ACCF/AHA Guidelines for the Evaluation and Management of Patients With Syncope. TL;DR: Watch Sonal’s syncope lightning rounds, and consider using the San Fran or Boston (both links) syncope rules. Use the FREE DOTPHRASE to help remind yourself of syncope patients who may required admission. The 2017 recommendations are the most evidence-based guidelines yet for the evaluation of syncope, and based on an extensive literature review and committee discussion which included emergency medicine physicians, ACEP, and SAEM! Studies report an estimated prevalence of a single episode of syncope at 19% of the population. Females have a higher prevalence of syncope, and those with chronic cardiac and vascular issues are more likely to have recurrent syncope. The most common cause of syncope is unknown in most cases (37%), followed by Reflex Syncope (21%), Cardiac Syncope (9%) and Orthostatic Hypotension (9%). The recommendations include a relatively worthless chart (above) showing how to initially evaluate a patient with syncope, recommending a detailed history and examination including orthostatics and evaluation for new murmurs, and a neurological exam. There is also Level B evidence that syncope patients should be evaluated with an EKG (This is a level A recommendation from ACEP). Given Cardiac Syncope has a high risk of recurrence and death, this seems appropriate. The article goes on to recommend targeted lab testing in any patient where the initial evaluation and diagnosis is not crystal clear. If you were here for Dr. Batra’s excellent discussion on syncope last year, none of this is surprising to you. The recommendations also discuss the use of many of the current Syncope Risk Scores, including the San Francisco Syncope Rule, Boston Syncope Rule, and Del Rosso (All three of these have Negative Predictive Values of 99%). This is probably the most important part, as we need to determine which patients are safe to discharge, versus those who should be admitted. When looking across all three rules, a few bit picture items come out; abnormal EKGs, a history of CHF or heart disease, age >65, and syncope either without a prodrome or while supine, are all concerning for higher-risk Cardiac Syncope. Additionally, we should consider alternative causes of syncope, including pulmonary embolism (DO NOT bring up the PESIT Trial), pregnancy, anemia/GI bleeding, and neurologic causes. As such, you can use the dotphrase below to help remind yourself of these potential causes, and reasons to consider admission for monitoring, Holter monitor placement, and potentially further workup. Dotphrase/MacroPt here with syncope/near syncope. Seizure less likely given history and exam. No neurologic deficits on exam indicating a stroke, and no signs of head trauma or injury. Given no signs of trauma or neurologic deficit, I will withhold further imaging of the head per ACEP Choosing Wisely Recommendations. Additionally, ACEP clinical policy on syncope evaluation recommends laboratory testing and advanced investigative testing such as echocardiography or cranial CT scanning need not be routinely performed unless guided by specific findings in the history or physical examination.

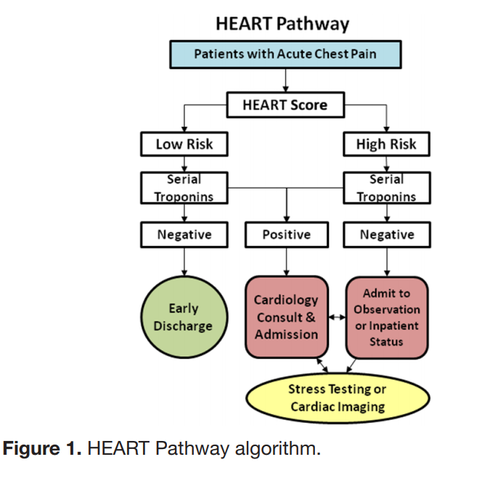

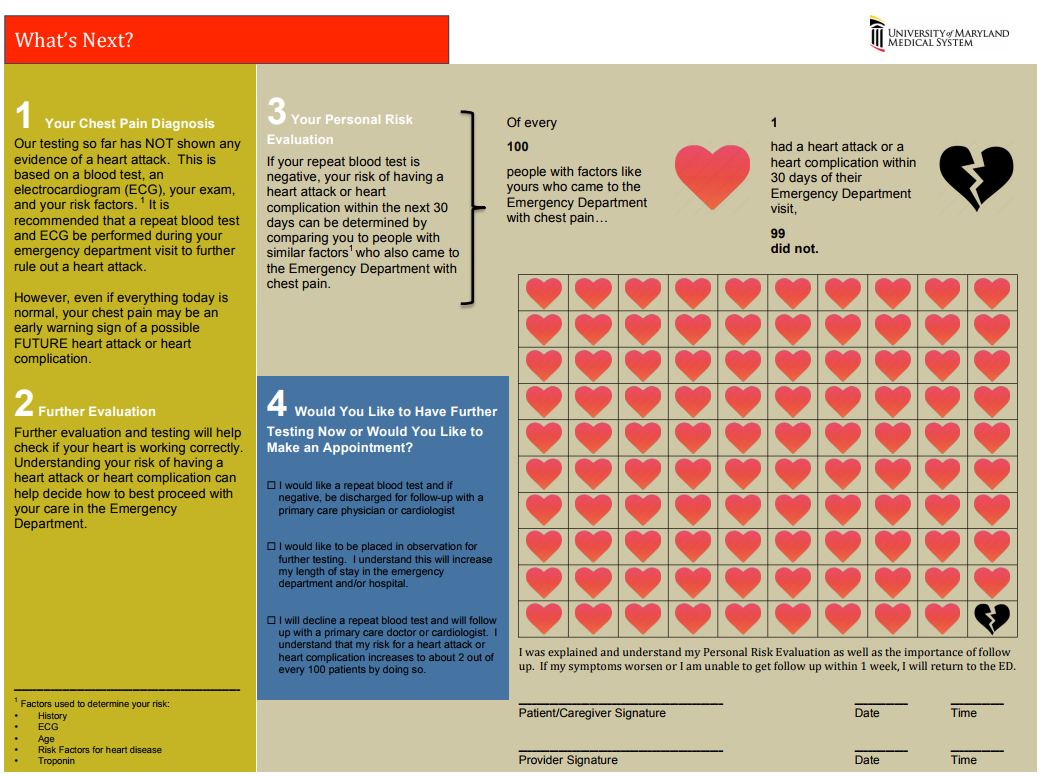

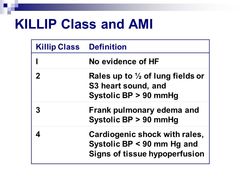

Patient’s history includes _ prior syncopal events, _ CAD, _ DVT/PE, _ seizures. Cardiac evaluation today shows _ murmur, _ JVD, _ peripheral pulses and _ lower extremity edema. EKG today _ without signs of Brugada or QT shortening or prolongation. _ PE risk factors. Neurologically _. Blood glucose _, _signs of hypoxia during event or currently, and _ intoxication complicating the patient’s presentation. Given this, the patient’s episode _. Risk Factors for Serious Cause: older age, pre-syncopal exertion, history of cardiac disease including heart failure, family history of sudden death, recurrent episodes, recumbent episode, prolonged loss of consciousness, chest pain or palpitations. Age >65, and Hct <30% San Francisco Syncope Rule (.ekmdmsanfran)CHF History Hct <30% EKG Abnormality SOB SBP < 90 mmHg at triage The “Delta Trop” is not a rule out test! It should be used in conjunction with the HEART score to have a conversation with the patient about risks/benefits of discharge vs admission during a low-risk chest pain evaluation. The “Delta Trop” refers to serial troponin testing, anywhere from 2 to 6 hours between the first and second troponin. As troponin testing has improved, the time between each test has been lowered. The most recent data recommends 3 hours between each troponin when the high-sensitivity test is used. The delta troponin is not a “Rule Out”; it is used in addition to the rest of the patient’s visit to help risk stratify them into low, moderate, or high risk chest pain. The HEART Pathway combines the patient’s HEART score with two serial troponins at zero and three hours. Observational studies showed 20% of patients with chest pain can be safely discharged utilizing this protocol, while maintaining a negative predictive value of Major Cardiac Event at >99%. This is actually a lower rate of MACE than the traditional HEART score alone (1.0% versus 1.7%). A recent controlled trial increased early discharges by 21.3%, decreased cardiac testing by 12.1%, and decreased length of stay by 12 hours! Just because we are discharging people, however, doesn’t mean they have been ‘ruled out’ for cardiac issues. Remember, 1% of those discharged had a major cardiac event within 30 days. The “Delta Trop” should be used as a shared decision making tool where the patient is provided the information and risks/benefits of admission versus discharge. Attached is the University of Maryland shared decision making tool, which is used in conjunction with a bedside discussion, to explain the risks and benefits.

Shared Decision MakingWhen you identify a patient with a low heart score (1-3) you can use this dotphrase to improve your documentation of your shared decision making conversation, and to make sure you are not forgetting alternative causes of chest pain. Remember, that by hitting “F3” your cursor will jump to the next “_” Patient HEART score 0-3, with risk of MACE 1.7% within 6 weeks, discussed with patient the potential for symptoms to be cardiac in nature and the need for follow up and return precautions. Other potential causes of the patient's presentation were considered; PERC _. Well's _. Pain not consistent with aortic etiology. Physical exam reassuring without signs of pneumothorax, pulmonary infection, heart failure exacerbation, or respiratory failure. Initial troponin negative. Discussed with patient the possibility of approximately 2% of an adverse cardiac event within the next 4-6 weeks, as well as options for further treatment, including observation admission, a second troponin at 3 hours, or discharge. After this discussion, the patient elected to _.

Pulmonary embolisms present with a broad variety of symptoms from chest pain to shortness of breath, and even fevers. Common exam findings include tachypnea and tachycardia. Risk factors include recent surgery, trauma, prolonged immobility, active cancer, birth control pills or hormone replacement therapy, or a history of prior embolism. Definitions

Pulmonary Embolism is the Arresting PatientPatients who arrest with a strong suspicion of pulmonary embolism may be treated with TPA. Bedside ultrasound should be used to help rule out alternative causes, such as tamponade or aortic dissection. Bedside ultrasound should also be used to evaluate for right heart strain prior to TPA.

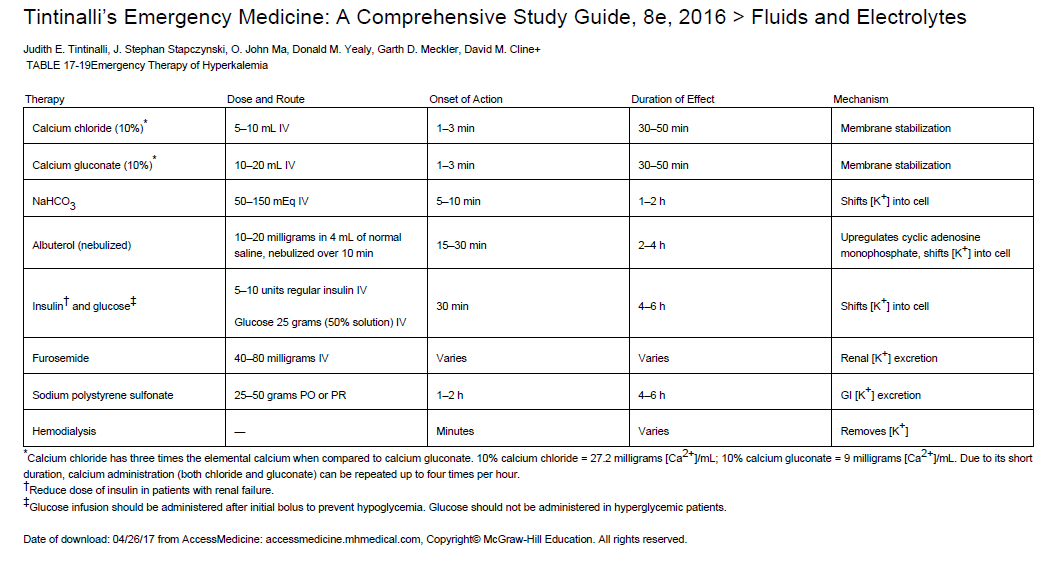

The initial dose of TPA in a cardiac arrest varies depending on what study is being evaluated. Some doses include an initial bolus of 10-15mg of TPA followed by an influsion of 85-90mg over an hour. Local protocol calls for a single bolus of 50mg over 2 minutes in cardiac arrest. This should be followed by at least 15-20 additional minutes of CPR to allow for TPA to circulate. A second dose could be considered. Current data shows that there is no difference in outcome when comparing patients who do and do not receive TPA during cardiac arrest. The same data also does not show increased risk of severe bleeding when comparing these populations. Undifferentiated cardiac arrest is NOT an indication for TPA. In patients with bradycardias or cardiac arrest, have a high index of suspicion for hyperkalemia, especially in patients with renal failure or hemodialysis. Death from hyperkalemia is typically secondary to diastolic arrest or fibrillation, and common symptoms include weakness, paresthesias, and nausea/vomiting.

Six common causes of ST elevation (J point 1mm above the baseline)

Evaluating for concerning causes of ST elevation:

|

Categories

Archive

February 2018

Please read our Terms of Use.

|

||||||||||||||||||