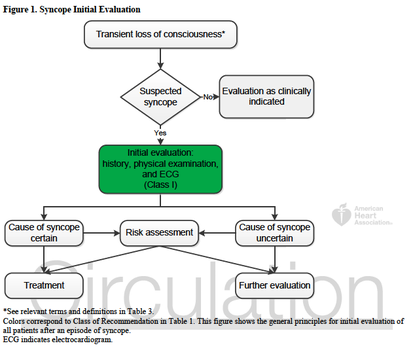

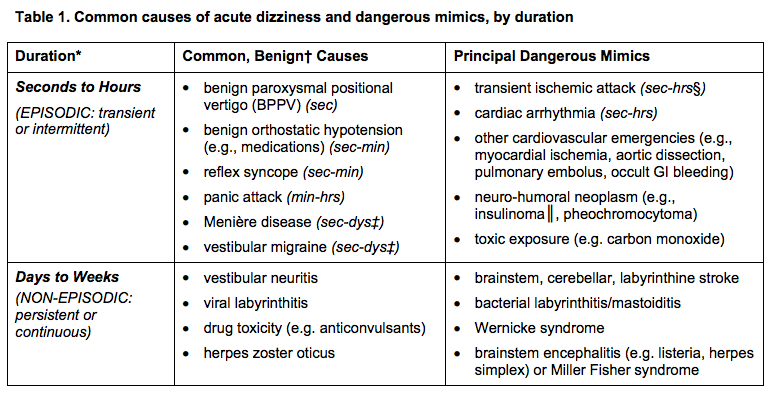

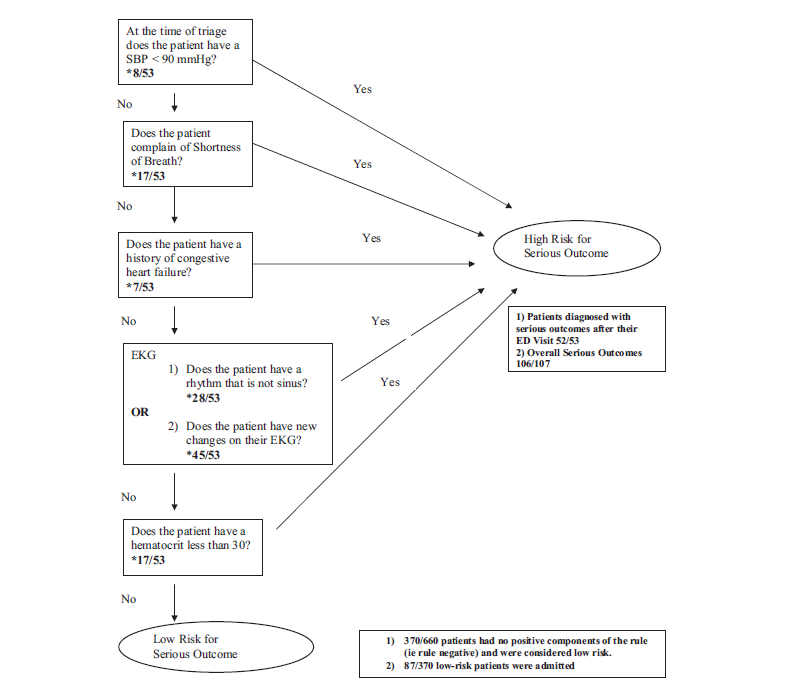

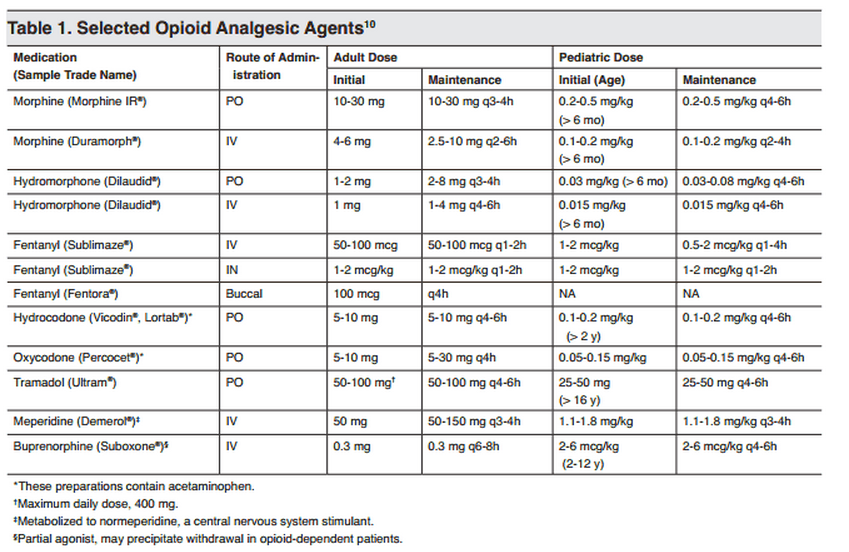

In-line with the month’s cardiology theme, this note from the TR desk will discuss the evaluation of syncope, and the brand new (2 days young) ACCF/AHA Guidelines for the Evaluation and Management of Patients With Syncope. TL;DR: Watch Sonal’s syncope lightning rounds, and consider using the San Fran or Boston (both links) syncope rules. Use the FREE DOTPHRASE to help remind yourself of syncope patients who may required admission. The 2017 recommendations are the most evidence-based guidelines yet for the evaluation of syncope, and based on an extensive literature review and committee discussion which included emergency medicine physicians, ACEP, and SAEM! Studies report an estimated prevalence of a single episode of syncope at 19% of the population. Females have a higher prevalence of syncope, and those with chronic cardiac and vascular issues are more likely to have recurrent syncope. The most common cause of syncope is unknown in most cases (37%), followed by Reflex Syncope (21%), Cardiac Syncope (9%) and Orthostatic Hypotension (9%). The recommendations include a relatively worthless chart (above) showing how to initially evaluate a patient with syncope, recommending a detailed history and examination including orthostatics and evaluation for new murmurs, and a neurological exam. There is also Level B evidence that syncope patients should be evaluated with an EKG (This is a level A recommendation from ACEP). Given Cardiac Syncope has a high risk of recurrence and death, this seems appropriate. The article goes on to recommend targeted lab testing in any patient where the initial evaluation and diagnosis is not crystal clear. If you were here for Dr. Batra’s excellent discussion on syncope last year, none of this is surprising to you. The recommendations also discuss the use of many of the current Syncope Risk Scores, including the San Francisco Syncope Rule, Boston Syncope Rule, and Del Rosso (All three of these have Negative Predictive Values of 99%). This is probably the most important part, as we need to determine which patients are safe to discharge, versus those who should be admitted. When looking across all three rules, a few bit picture items come out; abnormal EKGs, a history of CHF or heart disease, age >65, and syncope either without a prodrome or while supine, are all concerning for higher-risk Cardiac Syncope. Additionally, we should consider alternative causes of syncope, including pulmonary embolism (DO NOT bring up the PESIT Trial), pregnancy, anemia/GI bleeding, and neurologic causes. As such, you can use the dotphrase below to help remind yourself of these potential causes, and reasons to consider admission for monitoring, Holter monitor placement, and potentially further workup. Dotphrase/MacroPt here with syncope/near syncope. Seizure less likely given history and exam. No neurologic deficits on exam indicating a stroke, and no signs of head trauma or injury. Given no signs of trauma or neurologic deficit, I will withhold further imaging of the head per ACEP Choosing Wisely Recommendations. Additionally, ACEP clinical policy on syncope evaluation recommends laboratory testing and advanced investigative testing such as echocardiography or cranial CT scanning need not be routinely performed unless guided by specific findings in the history or physical examination.

Patient’s history includes _ prior syncopal events, _ CAD, _ DVT/PE, _ seizures. Cardiac evaluation today shows _ murmur, _ JVD, _ peripheral pulses and _ lower extremity edema. EKG today _ without signs of Brugada or QT shortening or prolongation. _ PE risk factors. Neurologically _. Blood glucose _, _signs of hypoxia during event or currently, and _ intoxication complicating the patient’s presentation. Given this, the patient’s episode _. Risk Factors for Serious Cause: older age, pre-syncopal exertion, history of cardiac disease including heart failure, family history of sudden death, recurrent episodes, recumbent episode, prolonged loss of consciousness, chest pain or palpitations. Age >65, and Hct <30% San Francisco Syncope Rule (.ekmdmsanfran)CHF History Hct <30% EKG Abnormality SOB SBP < 90 mmHg at triage

1 Comment

The QCS can be administered more quickly than the MMSE, and is easier to administer in the ED

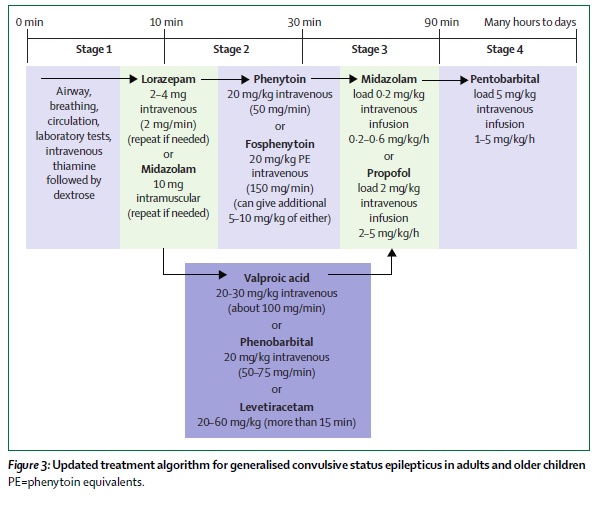

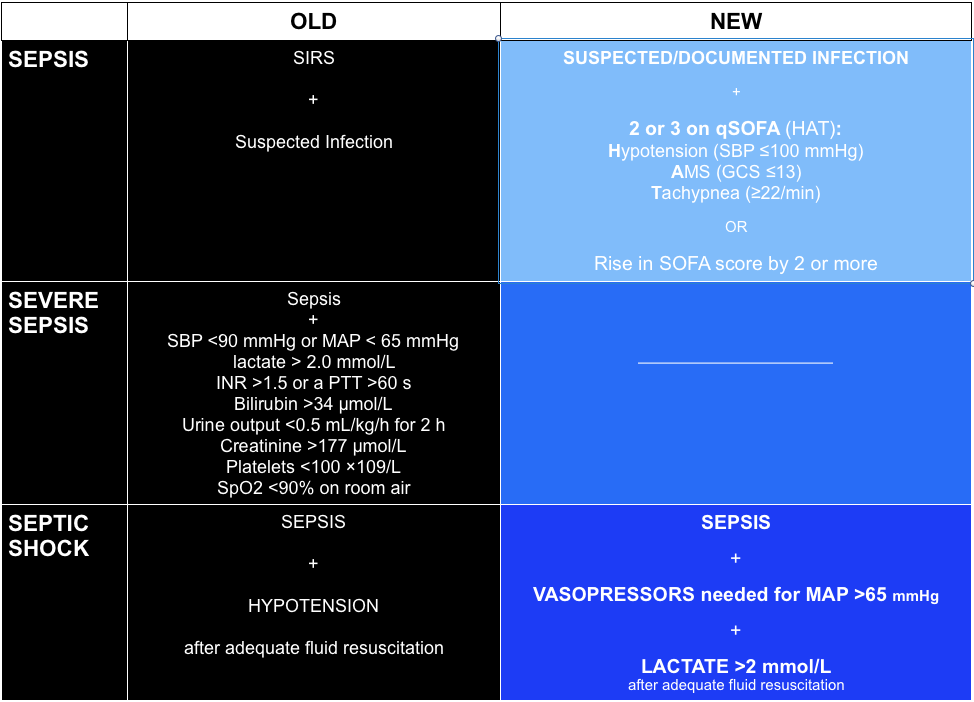

Status epilepticus is a common neurological emergency when a patient has a prolonged seizure or a series of seizures with incomplete return to baseline. The approach to status epilepticus has focused on early seizure termination, and rapid escalation of care to include general anesthesia when needed.

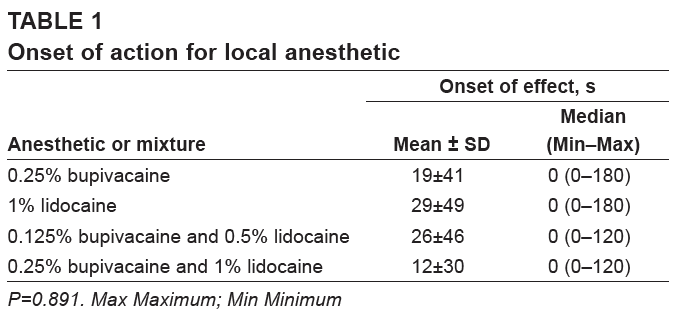

Status Epilepticus: A prolonged seizure or multiple seizures with incomplete return to baseline. Bupivacaine and lidocaine are often used concurrently, in theory, to combine the more rapid onset of lidocaine and the longer duration of bupivacaine. However, multiple studies, including a 1996 Journal of Podiatric Medicine article and a 2013 Canadian Journal of Plastic Surgery study have found no statistical difference between the anesthetics with regard to onset of action.

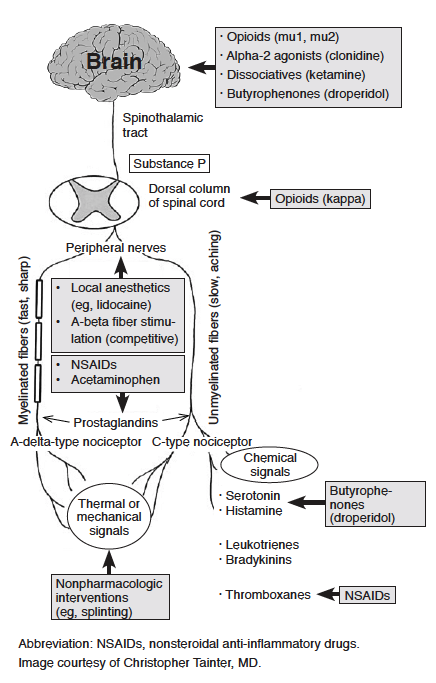

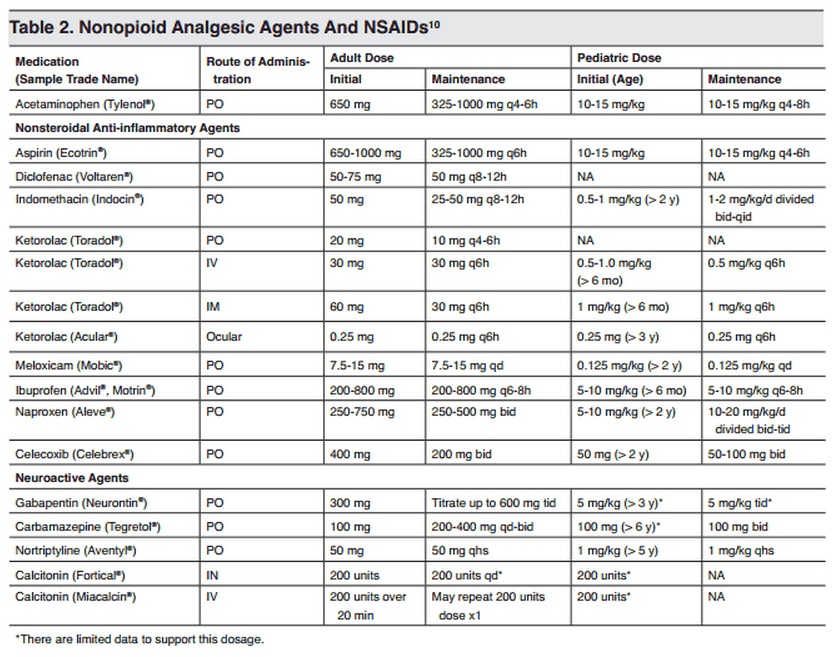

Naproxen With Cyclobenzaprine, Oxycodone/Acetaminophen, or Placebo for Treating Acute Low Back Pain1/6/2016 According to this new article from JAMA, the addition of Percocet or Flexeril to Naproxen does not improve functional outcomes in acute low back pain. The article compared functional outcomes in lower back pain at 1 and 3 weeks between Naproxen, Flexeril, and Percocet. Via a randomized, double-blind study in NYC, 323 patients were randomized to Naproxen + Placebo, Naproxen + Flexeril, and Naproxen + Percocet. Using an improvement in the Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ), the study found that adding cyclobenzaprine or oxycodone/acetaminophen to naproxen alone did not improve functional outcomes or pain at 1-week follow-up. These findings do not support use of these additional medications in this setting.

Can a CT read within 6 hours of headache onset can rule out SAH without the need for a lumbar puncture? This study found a 99% NPV of staff-read CTs in 11 non-academic centers with a 1/15,200 missed aneurysmal SAH. This study did not discuss the accuracy of resident or emergency medicine interpretations of CT scans.

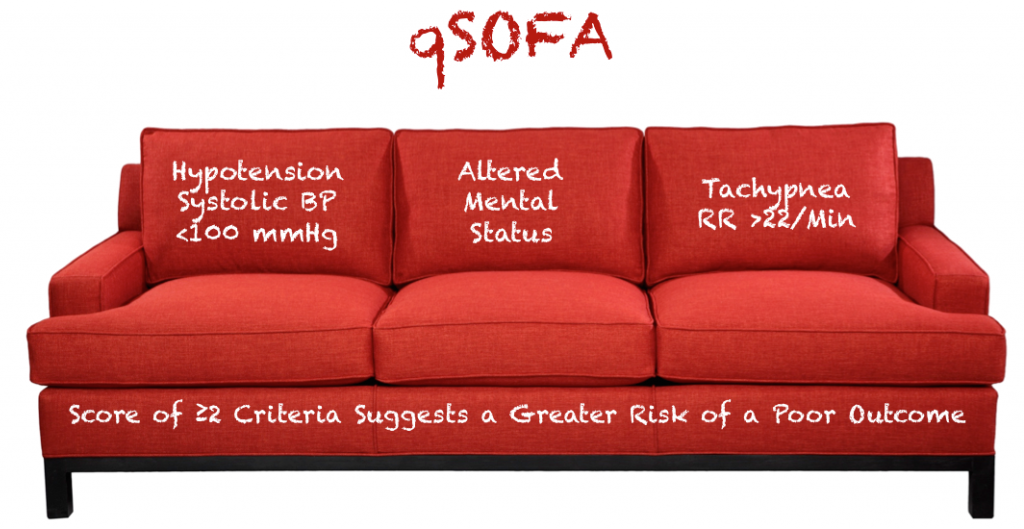

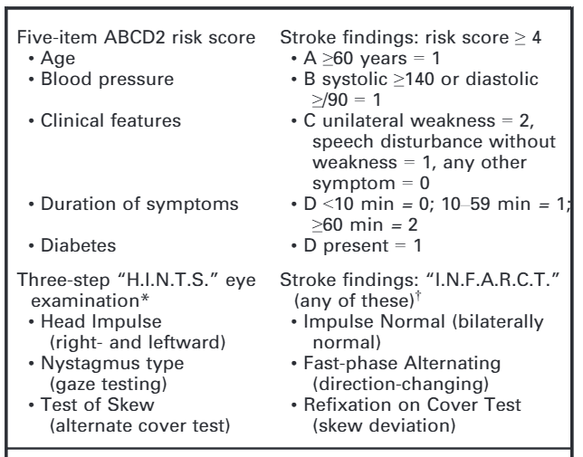

A multicenter, retrospective study of 11 non-academic centers. Included patients older than 16, with acute-onset headache of known duration without focal deficits or altered mental status. To be included, patients had to undergo a CT in <6 hours from headache onset and a lumbar puncture >12 hours from headache onset. 760 patients were included with 52 positive CSF findings. On review of CT imaging, 51 were considered negative, and only one perimesencephalic nonaneurysmal SAH was found, and no readmissions due to SAH. Adapted from a presentation by Ty Nichols, 12/2/2015 Dizziness can be difficult to assess in the ED given the vast range of etiologies and varying ways patients interpret their symptoms. Additionally, not all patients with emergency conditions will present with obvious focal deficits. A clinical decision making rule (HINTS) can help to more rapidly identify stroke patients to initiate acute therapies faster. The HINTS rule outperforms ABCD2 for stroke diagnosis in the ED when performed by qualified practitioners in patients with Acute Vestibular Syndrome. A mechanism to risk stratify patients presenting with syncope

The SFSR is criticized as being unsafe given a high miss rate (pooled sensitivity of 86%). Notably, there is one patient in the original trial who was SFSR negative and subsequently died (cardiac arrest after inpatient hospital discharge). Exclusion Criteria

|

Categories

Archive

February 2018

Please read our Terms of Use.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||