Mechanical Complications Treatment for mechanical post-MI complications includes vasodilators and ACE inhibitors, as well as blood thinners in cases which have thrombi.

Ischemic Complications

Pericarditis

0 Comments

Suicidal behavior, both attempts and ideation, are a common ER complaint, accounting for 4% of all visits. One million people in the US attempt suicide each year, and 1.2% of all US deaths are due to suicide. As the holidays are coming soon, I felt this would be a good time to review how we can ensure a safe discharge for those who may not meet inpatient criteria. TL;DR: ER interventions can decrease suicide attempts by 30%. Use the below dotphrase to improve your documentation in patients who are being discharged. A study published this July in JAMA Psychiatry found the implementing an ER intervention can prevent future suicidal behavior, with a number needed to treat between 13 and 22. The study utilized a primary (universal) and a secondary screening tool administered by the nurse and provider, followed by discharge resources and a follow-up phone call. The first step is similar to the current triage safety questions, asking patients about suicidal thoughts or attempts. Those who screen positive are identified and a secondary screening form (PDF) was completed by the physician. This form uses known risk factors for suicide to determine if there should be a psychiatric consultation (plan for suicide, intent, prior inpt treatment, and substance abuse). The third step of their intervention consisted of a safety plan which identified triggers for suicidal thoughts, how to get help, and what followup steps need to happen. All patients received a followup phone call after discharge. The study found that the intervention group had a 30% decrease in total suicide attempts than those receiving typical treatment. The study is interesting, but YOU DON’T NEED THESE FORMS TO HELP SAVE LIVES. Most of us are probably already incorporating most of this into our treatment of those patients being discharged with outpatient followup!

After initial evaluation, the patient endorses _ depressive symptoms. The patient has _ prior suicide attempts, currently _ abusing medications or drugs, and _ family history of suicide. The patient has _ judgement as evidenced by _, and displays _ insight into their symptoms. Although the patient is _ not currently endorsing active suicidal or homicidal ideation, and appears to have a good plan for follow up, I will consult psychiatry to provide outpatient resources and ensure a safe discharge plan prior to disposition.

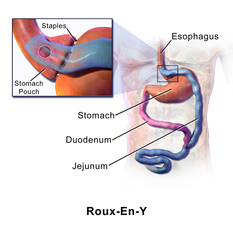

One-third of Americans self report as obese, and bariatric surgery has become a leading treatment option. Approximately 200,000 procedures are performed annually, most commonly gastric sleeves.

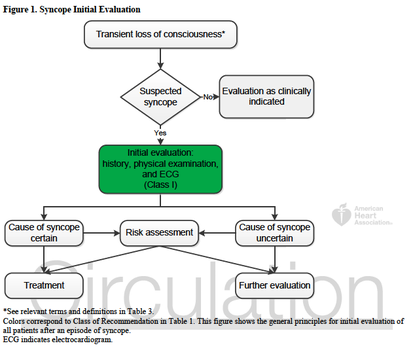

In-line with the month’s cardiology theme, this note from the TR desk will discuss the evaluation of syncope, and the brand new (2 days young) ACCF/AHA Guidelines for the Evaluation and Management of Patients With Syncope. TL;DR: Watch Sonal’s syncope lightning rounds, and consider using the San Fran or Boston (both links) syncope rules. Use the FREE DOTPHRASE to help remind yourself of syncope patients who may required admission. The 2017 recommendations are the most evidence-based guidelines yet for the evaluation of syncope, and based on an extensive literature review and committee discussion which included emergency medicine physicians, ACEP, and SAEM! Studies report an estimated prevalence of a single episode of syncope at 19% of the population. Females have a higher prevalence of syncope, and those with chronic cardiac and vascular issues are more likely to have recurrent syncope. The most common cause of syncope is unknown in most cases (37%), followed by Reflex Syncope (21%), Cardiac Syncope (9%) and Orthostatic Hypotension (9%). The recommendations include a relatively worthless chart (above) showing how to initially evaluate a patient with syncope, recommending a detailed history and examination including orthostatics and evaluation for new murmurs, and a neurological exam. There is also Level B evidence that syncope patients should be evaluated with an EKG (This is a level A recommendation from ACEP). Given Cardiac Syncope has a high risk of recurrence and death, this seems appropriate. The article goes on to recommend targeted lab testing in any patient where the initial evaluation and diagnosis is not crystal clear. If you were here for Dr. Batra’s excellent discussion on syncope last year, none of this is surprising to you. The recommendations also discuss the use of many of the current Syncope Risk Scores, including the San Francisco Syncope Rule, Boston Syncope Rule, and Del Rosso (All three of these have Negative Predictive Values of 99%). This is probably the most important part, as we need to determine which patients are safe to discharge, versus those who should be admitted. When looking across all three rules, a few bit picture items come out; abnormal EKGs, a history of CHF or heart disease, age >65, and syncope either without a prodrome or while supine, are all concerning for higher-risk Cardiac Syncope. Additionally, we should consider alternative causes of syncope, including pulmonary embolism (DO NOT bring up the PESIT Trial), pregnancy, anemia/GI bleeding, and neurologic causes. As such, you can use the dotphrase below to help remind yourself of these potential causes, and reasons to consider admission for monitoring, Holter monitor placement, and potentially further workup. Dotphrase/MacroPt here with syncope/near syncope. Seizure less likely given history and exam. No neurologic deficits on exam indicating a stroke, and no signs of head trauma or injury. Given no signs of trauma or neurologic deficit, I will withhold further imaging of the head per ACEP Choosing Wisely Recommendations. Additionally, ACEP clinical policy on syncope evaluation recommends laboratory testing and advanced investigative testing such as echocardiography or cranial CT scanning need not be routinely performed unless guided by specific findings in the history or physical examination.

Patient’s history includes _ prior syncopal events, _ CAD, _ DVT/PE, _ seizures. Cardiac evaluation today shows _ murmur, _ JVD, _ peripheral pulses and _ lower extremity edema. EKG today _ without signs of Brugada or QT shortening or prolongation. _ PE risk factors. Neurologically _. Blood glucose _, _signs of hypoxia during event or currently, and _ intoxication complicating the patient’s presentation. Given this, the patient’s episode _. Risk Factors for Serious Cause: older age, pre-syncopal exertion, history of cardiac disease including heart failure, family history of sudden death, recurrent episodes, recumbent episode, prolonged loss of consciousness, chest pain or palpitations. Age >65, and Hct <30% San Francisco Syncope Rule (.ekmdmsanfran)CHF History Hct <30% EKG Abnormality SOB SBP < 90 mmHg at triage |

Categories

Archive

February 2018

Please read our Terms of Use.

|

||||||||||||